The following is a transcription of a presentation made by Professor Thiebault Laurentjoye from Aalborg University Business School to the Scottish Currency Group 2024 Conference in Dunfermline. The full video of his presentation is here:

There’ll be a lot of ideas swimming around, but be confident, be open to having a clarity of purpose, and above all, I think be ambitious, because we need to deliver something that we’ve never had before, and that’s a country of our own. It’s time we did it.

To give you an idea, I’m currently in Bordeaux, which is pretty much the same, what is it, longitude as where you are in Dunfermline. And I’m absolutely gutted, I’m not able to be very in person, because first of all, I absolutely love Scotland and Scottish people.

I’m not going to say whether Wales or Scotland should be independent or not. It’s not for me to say, there are pros and cons. It’s a political choice, it’s what people decide. So in what is going to follow, I will use independence as a working assumption. So my job is, as an economist, to say how to make it feasible and as good as possible for basically the people and the countries involved.

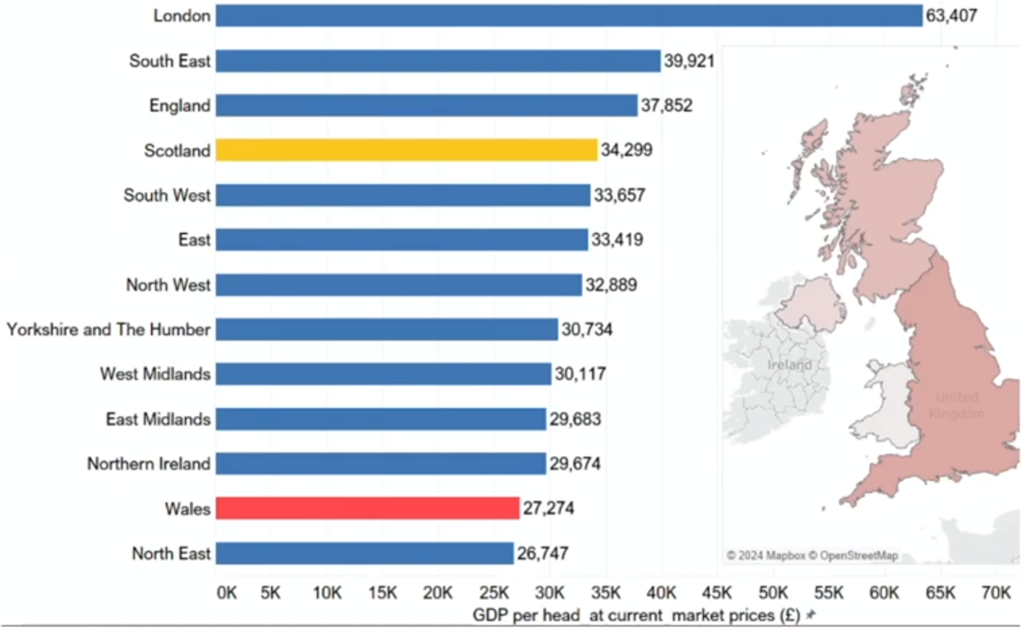

With that in mind, this is the situation of the UK. So just taking very simple metrics, GDP per head at current market prices. So as you can see, Scotland in yellow is actually doing much better than Wales, which is pretty much almost in the last position in the race, so to speak.

There’s actually a case to say that London should have a different currency to the rest of the UK, because frankly, London is the outlier. And I mean, having lived in central London, then in Watford, yes, I can say when going to, especially in the north of England, you would sometimes feel in a different country and I would say much more so than what could happen in…

Of course, there are disparities in France, but I would say that going from London to the Manchester Sheffield eads the area, sometimes could feel like being in a different country.

Okay, so the report currency option for an independent Wales was commissioned by the played Cameroon, a senate group in Wales. It was, next point, it was part of the submission of evidence for an independent commission on the constitutional future of Wales, which had previously asked how would an independent Wales establish its fiscal stability and credibility?

What currency would it use? How would it maintain the confidence of the financial markets in the immediate aftermath of separation and in the medium longer term? So that was the brief.

So that’s how the report is structured and I will go through these points in the presentation. However, just before, just in case someone has read the report is interested in reading it and just to give a bit more intellectual background and context.

I will go through basically the kind of dominant paradigm in kind of currency area formation analysis and which is something that I used when I was a student and even as a researcher, I’m still kind of evolving from that paradigm.

So it’s called the optimum currency area approach. It was developed in the 60s and 70s. But then because, as you may remember, the Bretton Wood system collapsed, everything became floating and there was a loss of interest for that theory.

But it reemerged during the inception of the euro area. So as of basically the 90s, especially the late 90s, there would be a lot of things to say about what was produced at the time.

But that’s not for now.

But basically, if I had to put it very simply, what the theory says is there are pros and cons in forming a currency area. The pros or the main pro is you reduce transaction costs, which consists of conversion costs between the currencies as well as exchange rate fluctuations.

On the downside, you lose, especially the exchange rate as an adjustment device and this requires substitutes in place. One of them is to have labor mobility or factor mobility in general. Another one is to have fiscal transfers between regions part of the currency area, so fiscal compensation.

So what is interesting is that from a technical perspective, the UK is an optimum currency area. It is, as a matter of fact, people can move from Wales to England to Scotland.

There is fiscal redistribution between England and other regions. We can always discuss the amount and the modalities. But the truth is, if you compare to the eurozone, for instance, it’s not even comparable. The scale is completely different.

So from a technical perspective, one could say, yes, the UK is an optimum currency area. There is very possibly a divergence in terms of the political perspectives and preferences between typically England and Wales and England and Scotland. And this is something that re-matters.

And the second point is that just the fact that you have those fiscal redistribution and labor mobility doesn’t mean that the situation necessarily is optimal because you could have an economic powerhouse, so typically London, draining forces, especially from Wales, draining all the grains, for instance, and then giving back money to Wales, but just to effectively subsidise an effective situation of economic underdevelopment.

And this is really something that I really realised while writing the report.

I have become somewhat critical of the theory over time, especially experimenting, modelling, but I really realised while writing the report that it does need quite a bit of improvement still.

Also, generally speaking, for everybody interested in macroeconomics,

there is this idea that you can treat fiscal and monetary policy as two entities that live their own life.

For instance, if you use the Moodle flaming model, it will say, oh, if you have a floating exchange rate, monetary policy is great, fiscal policy doesn’t work, whereas if you have a fixed exchange rate, fiscal policy is great, monetary policy doesn’t work.

So that’s literally what students learn when they do international macroeconomics. Also, coming from the same authors, Moodle and Flaming,

there’s this idea that you can, at the same time, have a fixed exchange rate, free capital movements, or capital integration, and independent monetary policy.

There’s nothing that’s said about fiscal policy.

This very well-known impossible trinity or trilemma does not talk about fiscal policy alone, because fiscal and monetary are supposed to live separate lives.

Fiscal and monetary policy are intrinsically interconnected.

There are so many ways of showing it, but just take the fact, for instance, that when you issue public debt, this has an impact on, obviously, interest rates on the market, unless the central bank intervenes in real time to neutralize the effects,

which, when you think about it, is an obvious form of monetary policy intervention.

So the government will affect interest rate conditions.

Also, interest rate changes through the political channel will put pressure, maybe, on governments. And also, regarding the point on fiscal policy being best in fixed-section rate setups, you will notice in the real world that there tend to be fiscal constraints, especially look at the eurozone. I mean, it’s farcical.

The amount of constraint put on national countries, it just deters any country from pursuing industrial policy, and it explains why the eurozone has been lagging behind the US, later on China, over the last 15 years.

And also, and that’s very, very, very important, and a point I will reiterate,

which in the report I called the Greek trap, but when the central bank does not cooperate and intervenes to smooth financial conditions to provide liquidity,

especially on sovereign bond markets, you end up with a situation where political entities, governments, will be at the mercy of market speculation.

And the extreme case is Greece in 2010, once it had been downgraded by rating agencies, when institutional investors could not hold the bonds anymore, then you could see spikes in interest rates, and that was highly problematic.

And this is really something any country, such as Scotland or Wales, which would want to become independent, really has to keep in mind. You don’t have your own central bank. This might happen.

So the report starts as follow. I talk about the well-known situation of twin deficits in Wales, a twin deficit being defined as the coexistence of fiscal and current account deficit.

So roughly, we’re talking about 13 to 15 billion pounds in 2022, which represents approximately 15 to 20% of Welsh GDP. The import and export patterns are slightly different, but somewhat alike.

Roughly half of exports and imports are to and from the UK, and imports 16% from the EU, exports 29% to the EU. We’re talking about Wales. This has implications.

When you have a fiscal deficit, you need to issue public debt. So you really need to think about it. Which currency will you issue in once you’re independent? And secondly, you need to think in terms of if you want to manage your exchange rate, you need to think about your foreign exchange reserves, because when you have a deficit, you’re going to run out of them.

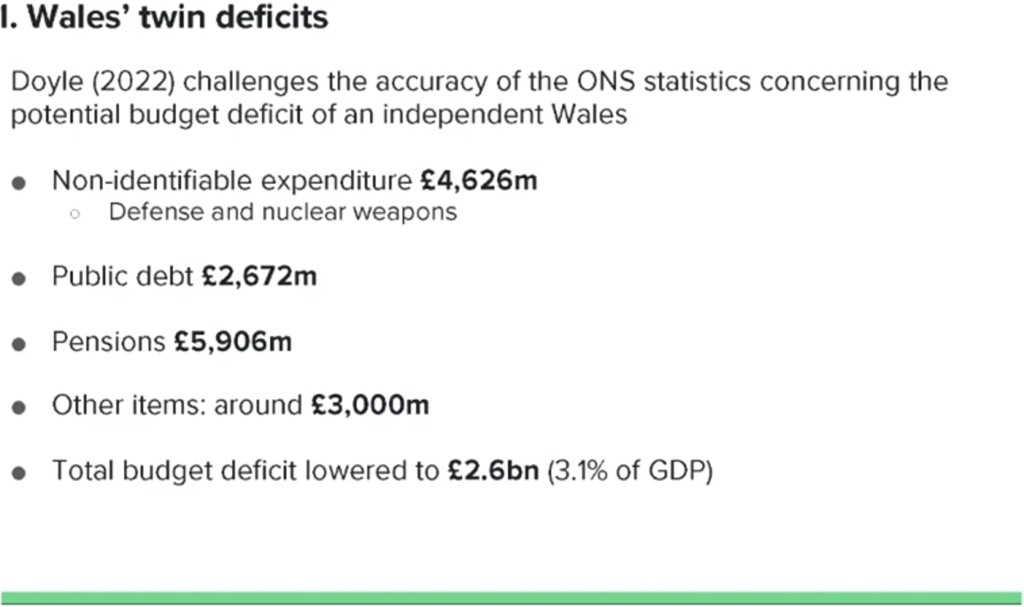

John Doyle, who’s from the University of Dublin in Ireland, also wrote a report for the Senate Commission. Actually, two reports last year. And in one of them, he challenges the ONS figures, basically. And going through the accounts in great detail, he identified a number of items that could very well have to be reassessed after independence.

I will go through the main ones.

Non-identifiable expenditure, four and a half billion pounds. So this is typically defence and nuclear weapons. This is something that really only England, like the core of the current UK, has an interest in because it’s to do with being a nuclear power, being in the permanent defence console of the United Nations. Public debt as well.

Wales would not inherit from the ratio of the existing public debt. So that would probably save the tune of 2.5 billion. Pensions as well, nearly 6 billion. Other items, 3 billion.

So that reduces, according to Doyle, the total budget deficit by more than 10 billion. So that’s quite a significant drop.

And I won’t say anything in terms of the trade and current account balance

because normally they tend to go hand in hand together, but the truth is the statistics are not granular and available to really be sure. However, one could reasonably assume that a lot of those things that count as imports

might be the counterpart of intergovernment services within the UK.

So it’s very possible that the current account deficit of Wales

would actually be lower after independence than the official estimate.

So then I go into the general considerations on the choice of a currency regime. There are six.

The first one is trade implications. I think that’s a very poor argument.

It basically says, oh, you should not use a separate currency because there are costs of using that currency. It’s not optimal. You should use a currency of a bigger area.

Then I just want to ask, how do you explain that Denmark, 5.5 billion people uses its own currency? Switzerland, no way, not Finland, they’re in the euro area. There are so many counter examples.

I think it’s not a very, very good argument. Monetary policy freedom is the second one. It comes from what I talked about earlier, the impossible trinity. It is, in my opinion, monetary policy on its own has been sort of overestimated. I would say it’s relevant, but only moderately so.

On the other hand, I would say that exchange rate as a policy tool is definitely something very, very important, not necessarily to use all the time, but to know that you have it just in case. This is what Greece missed back in 2010.

Had Greece kept its own currency, it would have been able to just devalue a strong devaluation, but it would have been outside of trouble much faster and probably in much more preferable way for its own population.

That’s why Denmark, for instance, is completely fixed against the euro, has been for 40 years and first against the Deutsche Mark, not against the euro, but at least they know they have an exit door if they really need.

Then there’s the point about destabilizing fluctuations. I will go back to that one.

I just want to say there is this tendency to only give the choice between two exchange rate regimes. Either you go for very, very fixed, hard, or you go for pure float. There are many intermediary possibilities. Again, I will go back to this.

Fiscal policy restrictions.

When you’re in the palm sterling area or if you join the euro zone,

there would be fiscal policy restrictions. It’s true, however, that only applies if you decide to join those areas.

Wales on its own would not be facing the same set of restrictions. The last one I think is actually the most underestimated in the whole literature. It’s only started to be considered seriously by a minority of economists and I hope this is going to improve over time. This is related to what I was saying earlier, that sort of independent life between fiscal and monetary policy and not considering the implications, the financial stability implications of fiscal policy.

Here, I would say the fact that when you have your own currency, you can be more in command of your financial conditions is extremely important, especially through the ability of the central bank to intervene. This is a point that really needs considering that is not talked about at all in theory, but in real life this is not something that needs to be done proactively.

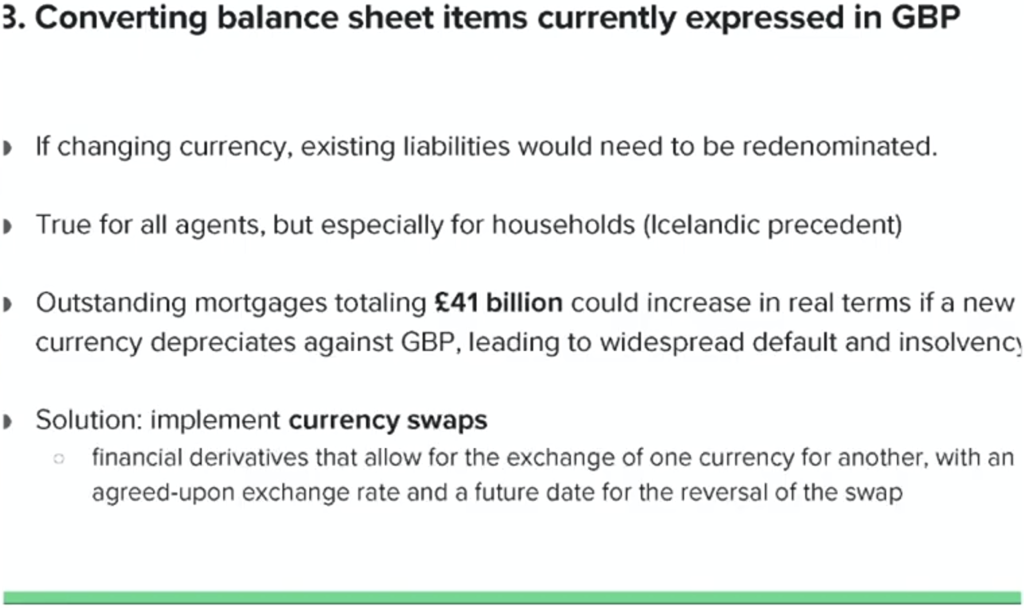

It’s to do with changing the currency in which some liabilities in particular are denominated.

If you issued a Welsh currency, the same would apply for a Scottish currency,

and if mortgages, for instance, were still in pounds, well, if your domestic currency depreciates against the great British pound, you would find yourself with real cost of repayment of mortgages going through the roof, and this is exactly what happened in Iceland in 2008.

So, obviously, especially for the most, so you can consider two types of agents.

You have agents that professionally deal with exchange rate risks, especially financial agents, and you have agents who have no idea what it’s about.

And the latter, obviously the biggest example is households, but you could also include small firms. Obviously for those agents, it is imperative to change the currency in which liabilities are denominated.

One straightforward solution is to implement something called currency swaps.

This is something financial agents know very well about. I don’t need to go too much into detail, but it’s basically doable. Okay, then I investigated the standardization defined as the belonging to the GBP area,

but without being a formal member.

So, basically, you accept the rules and you don’t have much of a say.

So there was the Scottish referendum in 2014. Scotland said, oh, we would keep the GBP, but Westminster said absolutely not. So then there was this plan B, keep using the sterling, but without a formal agreement.

So, I’m going to say it loud and clear, this is a terrible idea.

This is basically currency, monetary, fiscal, suicide in waiting, so don’t do that. Now, it’s interesting to see that in its 2022 report, which was called the stronger economy with independence, the Scottish government argued in favour of what they called a staggered approach to currency change, whereby Scotland would keep using the pound sterling until the time is right to move to a Scottish pound.

Okay, I am speechless. It’s literally, this is basically creating the conditions to never be able to issue your own currency, because you’re going to create so much financial instability, speculation, like this is awful.

I mean, I hope the people who wrote that didn’t write about climate change or because then don’t read it. By contrast, there’s a study from Common Weal that argued very sensibly in favour of introducing Scottish currency ASAP.

I will now go through the arguments in favour of staggered sterlingization. You don’t need to re-derminate the asset, no currency change. Then there’s institutional stability, technological, cognitive, operational, and there’s exchange rate stability.

Obviously no exchange rate risk, less fluctuations, while you don’t even need to change the currency, and it’s a source of confidence for investors. Now let’s comment on these arguments a little.

So the first one, it’s a double-edged sword, so actually the argument comes from Common Weal and it’s absolutely, it’s bottom.

If people expect that in the end you will issue your own currency, but you don’t do it in the first place, this is going to introduce expectations, like uncertainty, negative expectations that could turn into speculation.

Like if they know, oh, in a couple of years, you’re going to finally change the currency, alright. Whereas if you do it immediately, at least it’s done. In terms of institutional stability, there would be a lot of things to say. There will be transformations anyway, and you may as well use economies of scale,

like do everything at once in a consistent way instead of doing one, then the other, and so on.

Also handling of multiple currencies is already a thing. In terms of the exchange rate stability, again, there is this tendency to only oppose purely fixed versus purely floating regimes. I will go back to this.

Now the arguments against sterlingization.

So basically you would end up very constrained in your fiscal policy. I mean, Wales would end up very constrained in the fiscal policy. There’s a very likely currency of evaluation because you keep in an exchange rate of one to one,

when maybe what you would need would be a currency 10 or 20% weaker to be more competitive.

There wouldn’t be fiscal transfers anymore. Okay, that’s something to keep in mind.

So currently, technically, the UK is an OCA, but you would lose fiscal transfers.

So you would be using, I mean, Wales would be using someone else’s currency, but without the fiscal transfers.

So actually, there was some compared to the current situation in that respect. Also, they would be excluded from Bank of England asset purchase, and there wouldn’t be any intervention of the dedicated central bank in the form of lender of last resort or market maker of last resort. This basically opens the door to a lot of troubles.

So here, yeah, it’s a self-defeating strategy. It would actually make it harder to implement a Welsh currency further down the line because there would be a structural current account deficit, so reduction in foreign exchange reserves.

No possibility of devaluing, so the situation would remain bad unless they implemented a kind of internal devaluation like Greece did, and this is horrible from a socio-economic perspective, so I wouldn’t really recommend doing it.

Next point, I mentioned this already, and yes, the absence of a central bank being able to intervene and to stabilize financial conditions would be a disaster. And there are precedents, I mentioned Greece, there’s also Puerto Rico in the US.

There may be part of the US, like the 51st state of the US. They were left to their home, and they had to default in 2017 or 2018, so that’s really something to keep in mind.

Then there was the idea to join the eurozone. I should mention this is something that played canrew, some people felt strongly about it, they thought, oh, we need to join the eurozone. So I had to, well, this is definitely one thing where I sort of had to dampen their enthusiasm. All the more as having worked previously on the eurozone, I’m actually quite critical of the way it works.

So just the important picture here is you don’t join the eurozone overnight.

First of all, you don’t join the EU overnight. It takes at least a few years, and then once you’re in the EU, there’s another couple of year process to join the eurozone.

So you can count at least four to five years. So it’s not something feasible in the short run. And keep in mind that there are advantages to not being in the EU.

For instance, Wales or Scotland would be able to put tariffs on or capital controls that could be useful, especially in the early days.

Something to consider as well. Wales or Scotland, going in the eurozone, the rest of the UK would remain your trade partner. So you would basically anchor yourself to a set of countries that are not your main partner, and you would maybe probably fluctuate against your main partner. That’s a bit dangerous, especially in the short run.

And also keep in mind there are governance issues with the eurozone, and it’s happening right now. There are restrictive policy rules in place in the eurozone that are a disaster. Like, I’m not kidding. It’s awful.

It’s basically just preventing the eurozone from having any kind of ambitious plan for the future, and it’s still happening. So I would really not recommend joining the eurozone to Wales or Scotland. And the EU is pretty big on a free trade, so you would end up not being able to put in place things that could help, such as tariffs or capital controls, even temporarily.

Now I turn to the part about introducing Welsh Pound. Here are the arguments.

There are two, but they’re very strong.

The first one is what you can do from a political perspective. Your autonomy is maximum fiscal monetary exchange rate. I could have even added like financial regulation and also financial stability. You get a better grip over market conditions and you especially remove any risk of default on your public debt, as long as there’s no original sin, meaning the central bank does not borrow in a foreign currency.

So if you have the Welsh Pound or the Scottish Pound, do not borrow in euro, do not borrow in GBP anymore. That’s just risky for nothing. And that’s the main predictor of government defaults.

Now there are arguments against that you can read in the literature. So transition costs, exchange rate risks, loss of credibility, capital flights.

Transition costs.

It’s true, but it’s not that crazy when you think about it. And Wales would not be starting from scratch. It’s not like it’s a wasteland and you would have to build everything from scratch.

Exchange rate risks, it’s a strawman. Okay, there are ways of mitigating fluctuations. I mean, I could talk about China or even Japan.

There are many ways of going about it, but loss of credibility. Okay, this can be flipped on its head. Investors will prefer a country even if the currency is depreciating, if there’s a vision, a strategy, investors like that. Whereas if you stay in a union that is to your disadvantage and clearly you’re not consistent in your vision, investors will be scared. So I think it can be flipped on its head.

And the last one, capital flights. Yes, definitely, it’s a possibility. And against that, either capital controls or from the start, you do value significantly. Because once you’ve done that, you lower the expectations of further devaluation.

So that’s the seventh part. I talk about the diversity of exchange rate regimes. It’s a bit technical. Here, I will just give some high-level points. But it’s just to show that there are many different things to consider. The possibilities are multifold when it comes to devising an exchange rate regime. And I think many of them are completely underused currently.

You can define a central parity, fluctuations, bans around that, or sometimes you don’t even have a central parity. You can decide to beg again one or multiple currencies. You can use a crawling mechanism, which means a series of micro-adjustments. And also, you can play strategically on information disclosure, which Singapore in particular does.

So, for instance, if you are pressed, so if there’s an issue with the exchange rate,

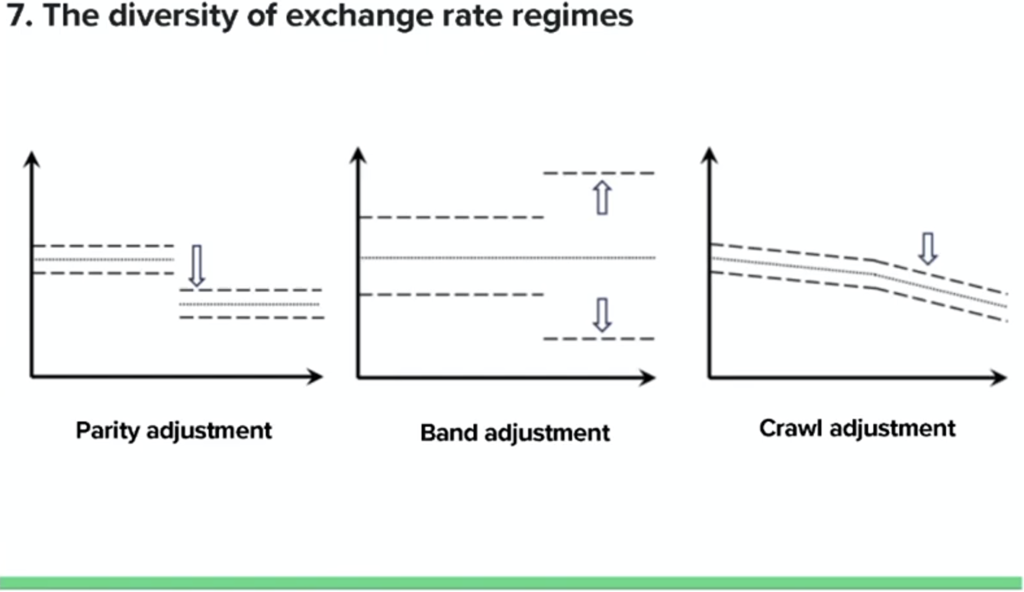

you need to devalue. There are several ways of doing it.

The first one I show here is through parity adjustment. That’s the best known. You just devalue, and you will move the parity as well as the bans. The bans will remain the same, and they just move along with the parity.

The second one, this is what happened after Black Wednesday. They went from 2.25 to 15% around the parity, which is creating a massive floating zone around the central parity. So, yeah.

But there’s a third possibility, and that’s the adjustment in the crawl, in the rate of crawl. And personally, of crawling things, they have been underused in the first world. Some countries around elsewhere in the world used them. China did that, especially after 2007.

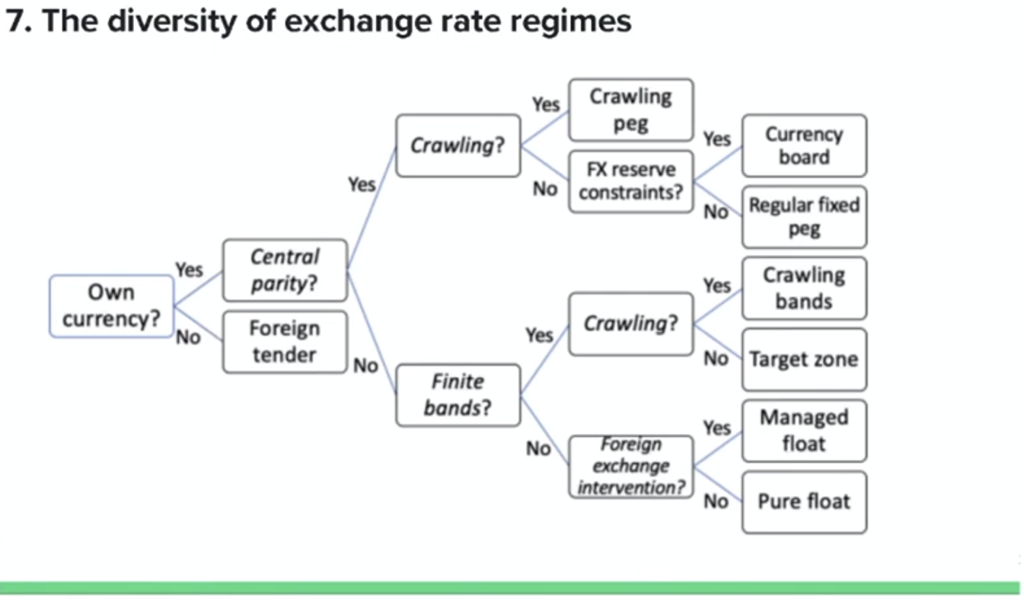

I want to have time to go through too much, but if you look at the… So, this is basically a decision tree to define your own, which currency, like exchange rate regime you want. So, I just want to mention that in the literature, usually there’s the choice between pure float, which is at the bottom right, and fixed peg, regular fixed peg. That’s the second from the top.

There’s also crawling peg as an option, and then you have one, two, three, four, five. Five other options, or four other options in the right column. So, just saying, there’s a choice. And so, it’s not a binary alternative.

This is how roughly the world is… I mean, some examples of organization. On the left, you have the hard fixed regimes. On the right, the floating regimes. In the center, all the intermediary regimes.

Notice that Bretton Woods was an intermediary regime. We had pretty good… Like, there was financial stability at the time. China, since from 78 to 2018, was in an intermediary regime situation. They recorded the best growth performance ever over a quarter of a century.

So, I’m just saying that there is actually a huge interest in looking at intermediate possibilities.

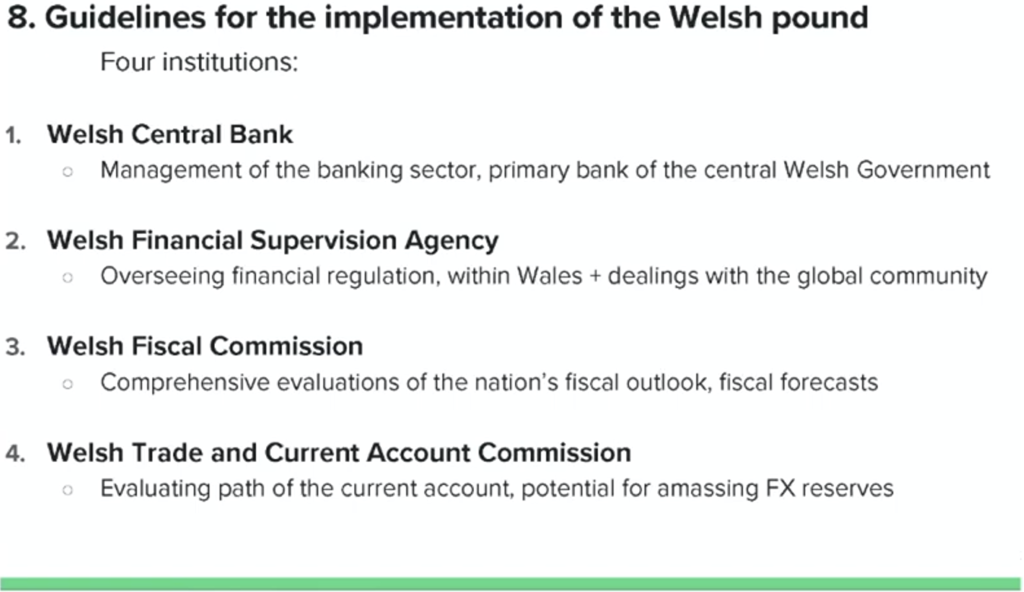

Guidelines for the implementation of the Welsh pound. I’m going to be honest. I think there are plenty of people more competent than me. More knowledgeable, especially as far as Scotland is concerned. And there are definitely other institutions to consider.

But in what I suggested, which again, was inspired greatly by the inception of the Euro, as well as the common real report. I suggested four institutions, Central Bank, Financial Supervision Agency, Peace Corps Commission.

I don’t want it to be too like a crazy watchdog, like the OBR, which will basically put restrictions on the government abilities. I don’t think that’s a good idea, but to have a body that provides reliable information is important.

And, but it should also have a counterpart in the form of trade and current account commission, especially as far as foreign exchange reserves and exchange rate management is concerned.

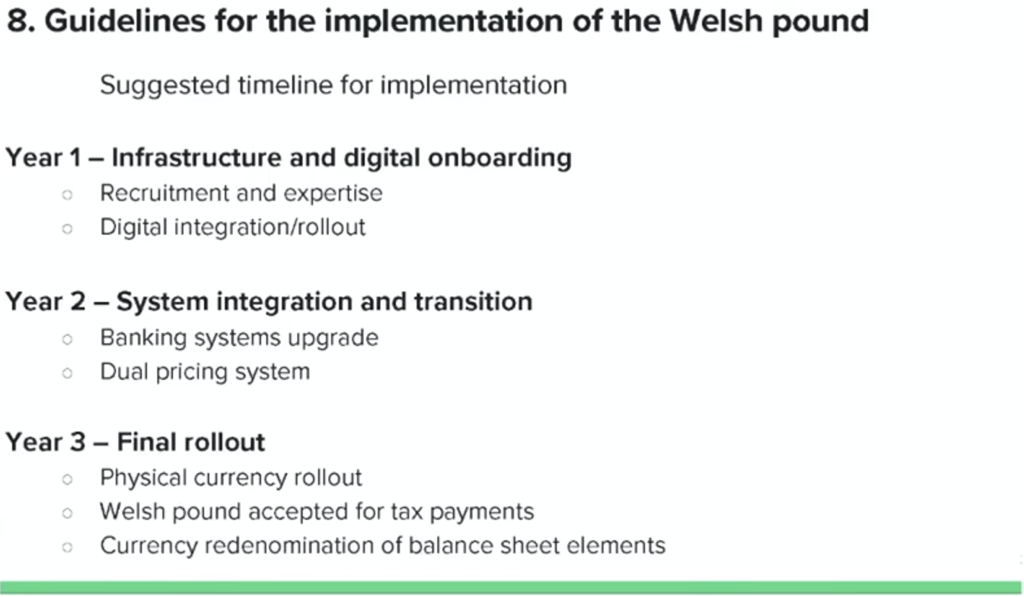

The suggested timeline, the main items, year one, you need to hire people and you can implement the unit of account from a digital perspective.

Year two, you upgrade your banking system. You start implementing your pricing, meaning people go to the supermarket, they will see the two currencies. When they get a bill, they will see two currencies and so on.

Year three, final rollout. You would have the physical currency available. You use it for tax payments. And obviously you need to have really denominated the balance sheet elements I mentioned previously. I know that was very fast for a three year thing.

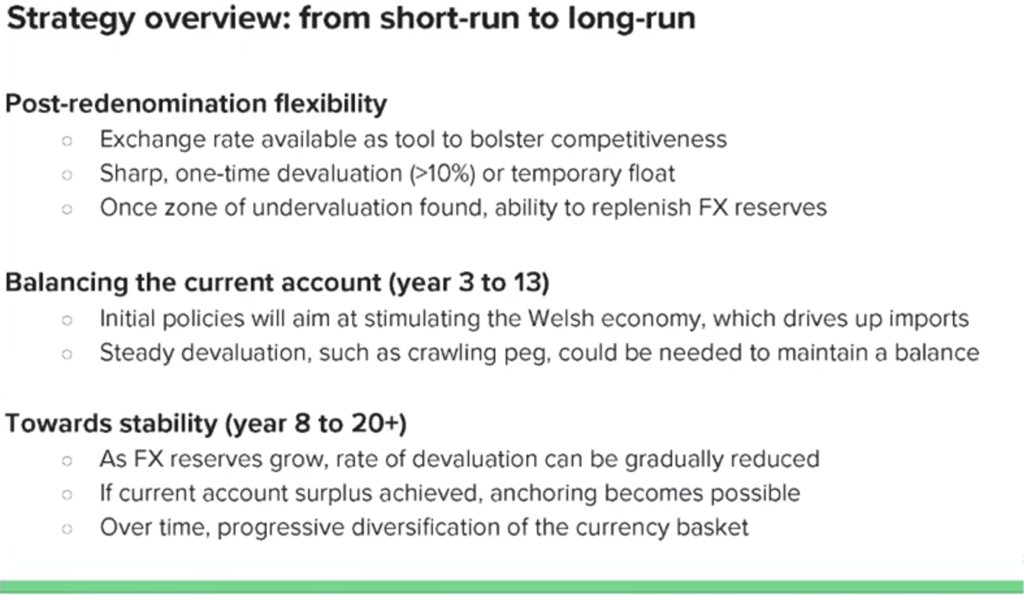

And this is something I did at the end of the report about like longer term strategy. And so once you really denominated, then you’re able to use the exchange rate as a, as a proper tool.

So I would say in the case of Wales, I think a devaluation of at least 10%. I wanted to write 20%, but it’s probably very necessary because Wales will need to become more competitive to sort of re, yeah, to rebalance its trade and capital current account.

Ideally, you may consider different options that won’t go too much into detail.

But the main idea is when your exchange rate is too high, you’re going to lose,

you’re going to have a current account deficit.

You’re going to lose foreign exchange reserves. When it’s low enough and you maintain it low, that’s typically what China kind of did like 20 years ago. You will then be able to replenish your foreign exchange reserves. And once you have those foreign exchange reserves, subsequently you will be able to defend the peg

that you decide to implement.

That’s for instance, why Denmark is able to have a very fixed peg and be very economically successful.

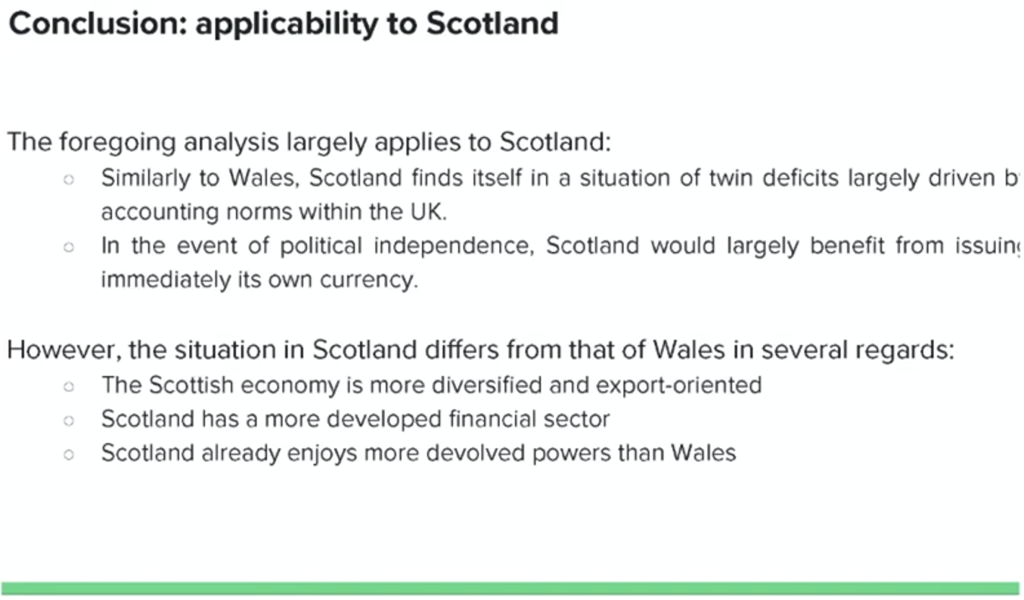

How does it apply to Scotland? I think a lot of it applies to Scotland. I mean, I don’t think I need to convince you too much. However, let’s face it, the situation of Scotland is different from the data of Wales.

Scottish economy is more diversified, export oriented. There’s a more developed financial sector and it already enjoys more devolved powers than Wales. All those points tend to Scotland being better prepared, better equipped for currency transition.

And I think it would make sense for Scotland to become independent first

rather than Wales doing it, because Scotland would be able to pave the way

and maybe even help Wales.

And I would say, especially in the event, that’s the last point, especially in the event when England didn’t play a very cooperative game with the two new independent countries, I think they would probably have to adopt cooperative policies.

Thank you very much.

Q&A

What sorts of things might you do in the first five years of an independent nation to create maximum predictability for international finance markets?

Regarding a lot of information, yes. So I forgot to mention, but this is the first time I present the report, because unfortunately last year, I was supposed to present it in Wales, but the plans changed, and so I thought that was a lot of information.

I’m aware I probably went very fast on certain aspects, and I’m sorry, but if you have any questions or you can ask the organizers about my details, if you can read the report, you can write to me if you have any questions. I’d be very pleased to talk further.

Okay, in terms of creating predictability, all right. So that’s an interesting question, because I think the answer here is really twofold, and I’m going to be very blunt. There’s this idea in… Even in mainstream economics, and I think that’s a valid point of mainstream economics, that the most powerful policy moves are the ones that are not anticipated by the markets.

So I would say, actually, you need to create predictability and how to do it, okay. You need to have a plan in terms of everything in a country-related, especially trade-related. You need to be able to have forecasts on what your inflows and outflows will be as far as incomes are concerned.

So obviously the state pension would probably be managed by… Now we’re talking about Scotland, would be managed by the Scottish government, but what about the private pensions? It’s very likely that people would receive payments in Great British Pound.

And so all those things, obviously, we need to be considered, you know, put into spreadsheets, plans, and so on and so forth. So this way, you create… You show, okay, we’ve got a plan. We know where we’re going. You would probably need to change your tax system, like to make it more consistent with the political orientations of Scotland to make it consistent for a standalone country.

Probably the Scandinavian model as a whole would probably be a good influence.

At the same time, keep in mind that you may want to keep some room for surprises. So if you divulge everything, the financial markets will anticipate

and sometimes misinterpret. Let’s face it, they’re not perfect.

So you want to be strategic in how you divulge information. And one aspect I didn’t delve into details, is Singapore, when you look at their exchange rate regime.

So Singapore, they have no central official parity. So they have a band, okay, there’s a band. That band is defined against a basket of currencies, okay. And it rolls, okay.

So you have a band that crawls against a basket of currency.

Now get this, neither the width of the band, the composition of the basket of currency, and the speed of the crawl is officially disclosed. So basically from an external perspective, they may as well be floating, it will make much of a difference.

And you can play on that.

And sometimes you can surprise the market and sometimes it’s actually the right thing to do. Although I know we talk a lot about, you know, being transparent and so on and so forth. But the truth is sometimes it’s not the best thing to do. So I would say yes, you need to provide a consistent picture, but you also need to keep in mind that sometimes CTA circumstances will dictate otherwise and you need to have a few alternative plans and you ideally should not disclose everything to the markets beforehand.

And I know that’s controversial to say. That was a wonderful presentation. And there are various technical points which I think I would like to follow up on. You’re very, you’re replying to the first question, immediately had me thinking about Keynes and thinking about his preference, and indeed the way Singapore works,

his preference for autonomous organisations which are free from political control

but guided by wise people. And perhaps that’s an objective which we could reach in Scotland. It would certainly be different from what happened in Brexit.

Does Denmark provide a good template for Scotland in the future?

Thank you very much for the question. Okay, really in the first part, yes.

Okay, so that’s actually one of the… I think Keynes was influenced by Edmund Burke in that respect. It’s something I actually think about sometimes

because some people might say, oh, but having those institutions managed by wise people, is that really democratic?

Then I look at some democracies and I look at… Yes, let’s say stupidity presiding over democracy and I’m thinking, oh, I don’t know what’s the best way forward is,

but I surely sometimes wonder how to strike a balance between openness and ability to reflect people, the will of the people, and at the same time ensuring a certain level of… Not just expertise, but competency.

But competency in a competitive way as well, not just something centered around a micro-cosmic sort of group thing as can happen, for instance, in economics or even in places like the European Union, to be fair. But yes, it’s an interesting point.

So here’s my take on Denmark. First of all, they were a little bit lucky because in the 70s they discovered oil and gas. So they re-suffered through the first oil shock in 73 and 4, as many countries did, including the UK.

They did better during the second one and from the early 80s onwards, they were able to use those fossil fuel reserves and that improved their trade and current account position. However, this is not the only factor. Because it’s true, they kind of were in trouble.

Let’s say they were in chronic deficit before and there were lots of social tensions. In the 80s, they decided to fix their currency, but they devalued in the first place.

They fixed their currency. They have a relatively high rate, especially on income tax.

They don’t have national insurance contribution equivalent, but they have a very high income tax rate. It’s 45% for average people.

And what that does is a bit like Germany. It will constrain the purchasing power of people. So from that, they will not overspend and that will reduce the kind of leakages through imports.

So I think those two factors, the fact that they… I mean, three factors, the oil and gas discovery, fixing the exchange rate lower in the first place and the tax system.

And you could add as well that they have this very strong sense of… Well, they are quite nationalistic, you could say.

It means that it kind of ensures this kind of socio-economic integrity. I should add as well trade unions are extremely important in Denmark. They are compulsory.

So when I joined the University of Oslo, and keep in mind I was in the UK before,

so pretty much the polar opposite. You don’t have unions in most places, but I was contacted by a union representative that even negotiated some of my pay on my behalf. And that’s why you don’t have Amazon, you don’t have Uber officially operating in Denmark. It’s because a union membership is compulsory and those companies didn’t want to have unions to deal with unions. So Denmark said, well, sorry, we won’t have you here.

So,Yes, I would agree. There are some lessons to be learned from Denmark. There might be differences, but I would say yes in a way. The same way I kind of see Denmark as this northern, more rich version of Germany. I’m not saying Scotland is richer than England, for instance. It might be richer than England on average.

There will be definitely parallels to draw, yes.

Leave a Reply