Scotland and England are going their separate ways – even without Independence. Look at voting preferences and social attitudes and it’s clear – Scotland and England are diverging. And have been for some time. Is Independence inevitable?

However you look at it, Scotland and England are different – and increasingly so. Here the author discusses political differences, and some important distinguishing social attitudes.

Political differences

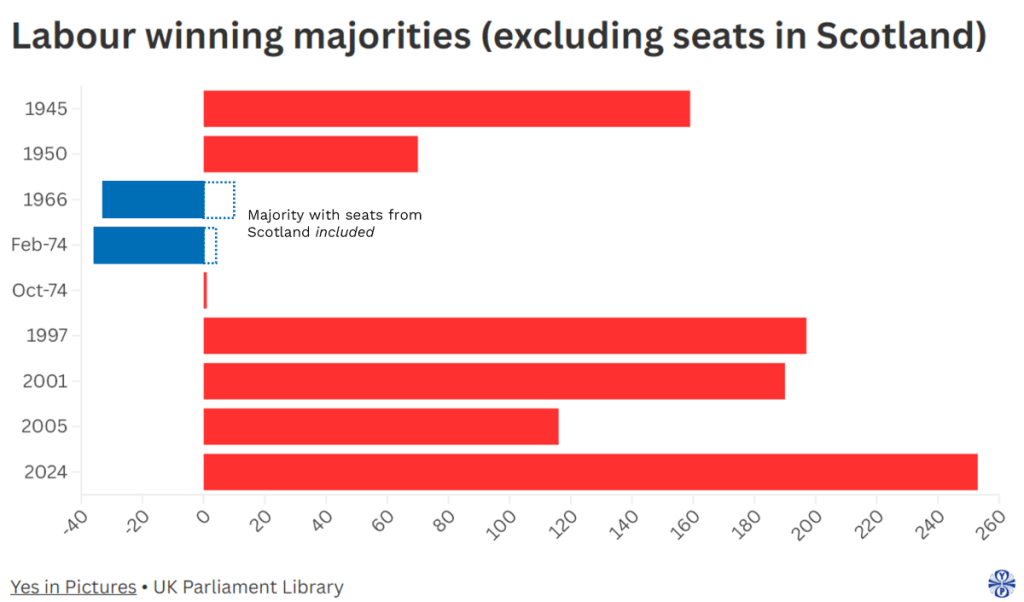

People (mostly) vote for parties who’s policies they would prefer to see delivered. In the UK – with its grossly antiquated First Past The Post system – occasionally there is large scale tactical voting that disrupts this neat assumption. The Westminster 2024 election and Scottish voting is a good example: Labour spent big with a message that only they could dislodge the Tories from power, when in reality every piece of data showed that Labour didn’t need Scottish votes to do this – and has virtually never needed them for power in Westminster.

But mostly people stick with party preferences. Polls after the Westminster 2024 election show voters returning to The SNP and Scottish Greens from Labour.

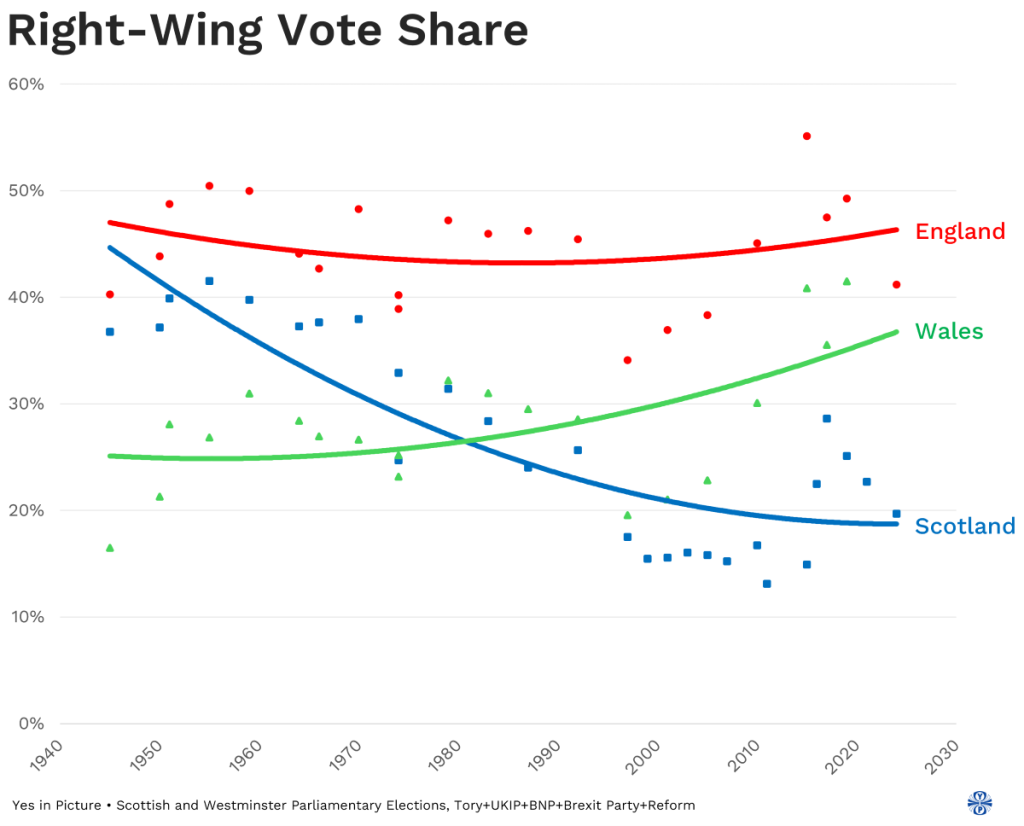

So what sort of policies do the voters of the different nations prefer? Let’s look at the trend in right-wing vote share (and hence also corresponding change in left wing/centrist vote share).

Firstly, you’ll see that Labour’s 2024 “vote for us to get rid of the Tories” message didn’t affect the right-wing vote (at least in Scotland). Instead, people temporarily moved their preferences from The SNP and Scottish Greens.

Secondly, and more interestingly, is the extent to which the three nations vary in their preferences for right-wing parties:

- England has maintained an unchanging and large preference – almost a half of voters – for right-wing parties;

- Wales has shown a gradual increase, starting to approach England’s keeness for the right win; and

- Scotland, however, has shown a steady and dramatic drop, more than halving support for right-wing parties over this period.

Even people who are tribal about seeing the UK as “one nation” can’t deny these fundamental differences.

Incidentally the author chose to plot right-wing vote share here, because each nation (other than England) has strong national parties that are all progressive and left of centre (think The SNP, Scottish Greens and Plaid Cymru). Conversely each nation (other than England) doesn’t have significant right-wing national parties – they all come from England. So this is more normalised view across the UK. Of course, this fact tells a story in itself, with a narrative that also helps to explain some of the trends shown above.

Before we leave right-wing vote share trends lets come back to Wales and Scotland for a moment. Note how Wales shows a steady decline until about 1999 – then a rapid rise. Whereas Scotland continues its downward descent. From Scotland’s perspective this is when its Parliament was re-established at Holyrood and significant powers devolved. Arguably initially Labour – but for most of the period since, The SNP – have protected Scotland from some of the excesses of Westminster’s continuing move to the right. Perhaps this has allowed Scottish voters to see and appreciate that the benefits of progressive policies can be feasibly delivered.

Social attitudes

Social attitudes drive political preferences. And to some extent vice versa. Since at least the times of the Scottish Enlightenment [ref], Scotland has demonstrated more progressive social attitudes than England. England has suffered the full onslaught of successive right-wing governments in all areas of society and perhaps this is in part responsible for maintenance of those popular rightist attitudes.

But some differences can be seen much earlier – for example, contrast Scotland’s “Poorhouses” with England’s “Workhouses”. Poorhouses were quite deliberately not places where you were forced to work in cruel and degrading conditions in return for food and a place to sleep. In fact the reverse – you were granted a place if you couldn’t work and hence needed somewhere to live. This progressive attitude dates back as far as the 15th Century [ref].

So let’s look at two important areas of social attitude in more detail: immigration and Europe.

Immigration

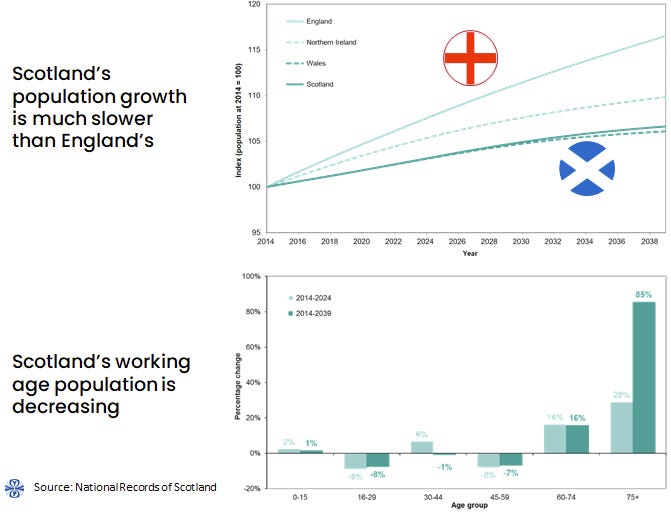

Scotland needs immigration for its strategic security. Its population growth is much slower, and its working age population is decreasing:

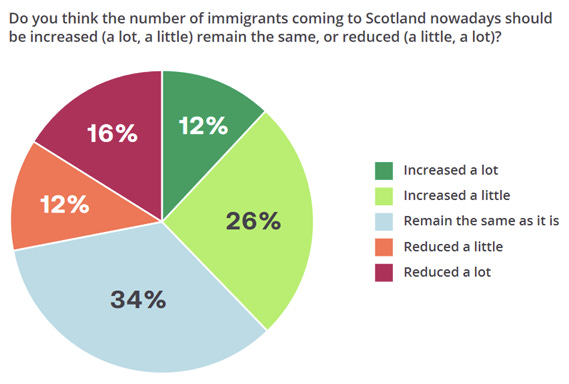

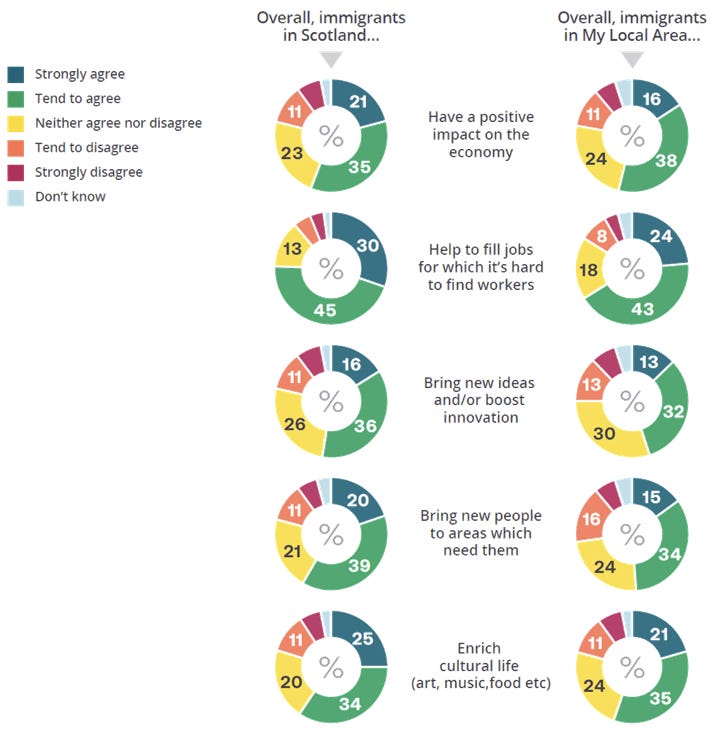

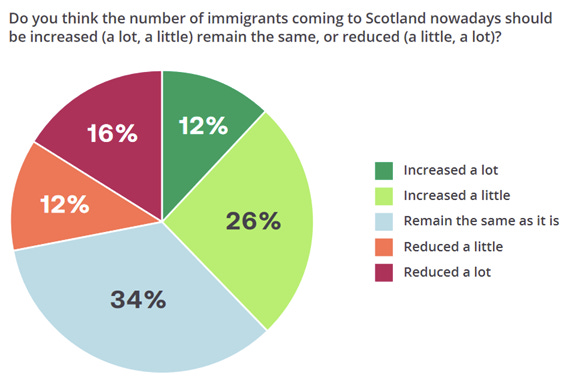

Some people understand this – certainly our Government is happy to tell us this reality (unlike in Westminster). But a recent analysis from Migration Policy Scotland – “The Migration Policy Scotland Attitudes Survey” [ref] – suggests that there is a more fundamental aspect of Scottish attitudes that recognises the value that immigrants bring.

And yet Scotland sees a nonstop diatribe of anti-immigrant rhetoric from Westminster – whichever party is in power. A rhetoric over which Scotland has no influence.

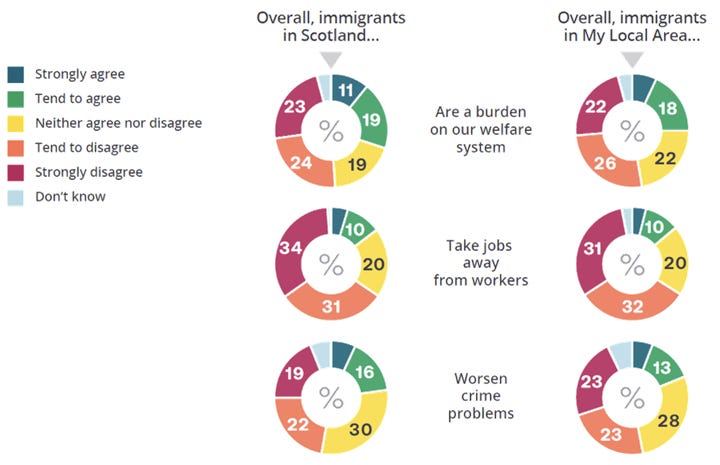

Westminster continues the anti-immigration rhetoric that they believe most voters in England want to hear

Europe

Did you spot that Labour Manifesto pledge in the picture above – “There will be no return to the single market, the customs union, or freedom of movement.” Yet more “making Brexit work”.

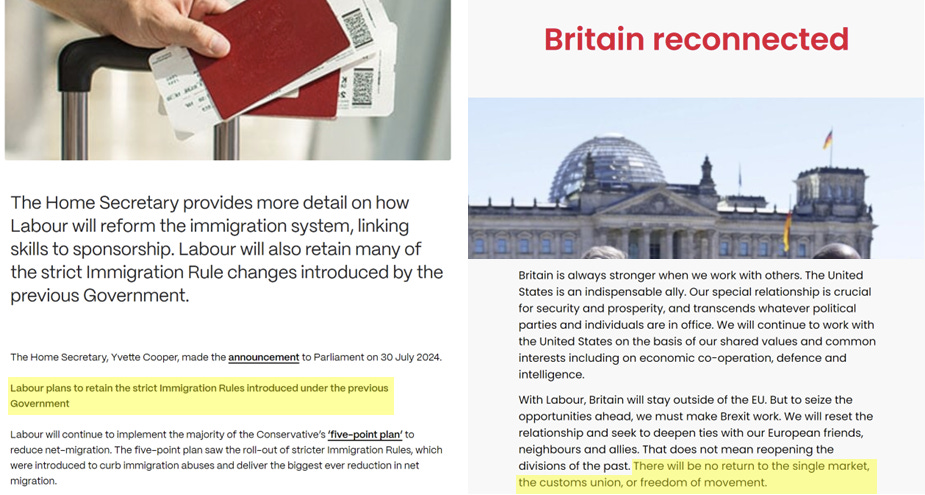

All areas of Scotland voted to remain in the EU and our Parliament rejected Westminster’s hard Brexit [ref]. Levels of support for rejoining the EU have continued to grow and a significant majority now support this [ref].

Unlike in England, our Government shows no equivocation over the benefits and necessity for Scotland to be back in the centre of Europe [ref]. Our most popular party campaigns with this clearly in its Manifesto. In fact, The SNP’s Manifesto pledges at the last Scottish Parliament election were very clearly stated [ref]:

- Choose Scotland’s future in an Independence Referendum; and

- Maintain and strengthen Scotland’s relationship with our EU partners with a view to rejoining as soon as possible.

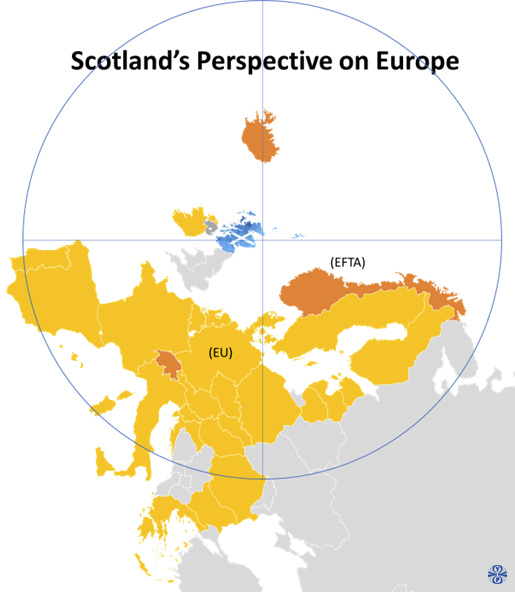

Scotland has historically held a very close relationship with Europe – from the “Auld Alliance” with France against England in the 13th Century [ref] to the strong Viking presence from Shetland and Orkney down. No surprise when you view the map of Europe slightly differently to how its normally shown:

Scotland is often spoken about as more like a Scandinavian country in outlook, rather than a country from the Anglo-Saxon heritage of England.

Leave a Reply